Even though many of them call themselves non-believers, a large number of Danes still use the Church’s spaces and rituals for life’s major events. But what if you just do not feel like using the framework of the established church, but still need a solemn and meaningful space for a funeral? Meet the architect, Katrine Lyn Andersen. In her degree project she created a secular burial ground as an alternative to the traditional cemetery: a burial ground that is meaningful, whatever your view of life, formed by nature and the city, and with room for grief and contemplation.

What is your final project about?

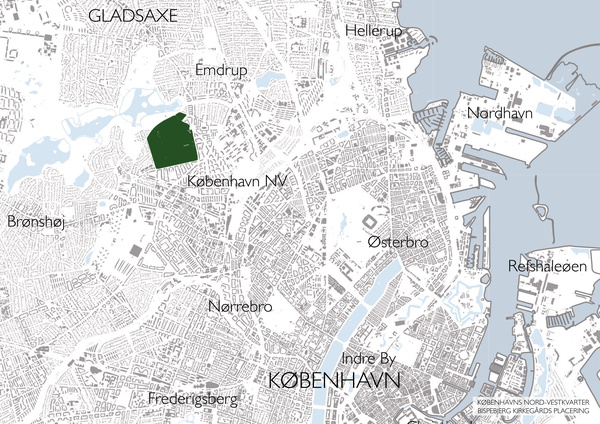

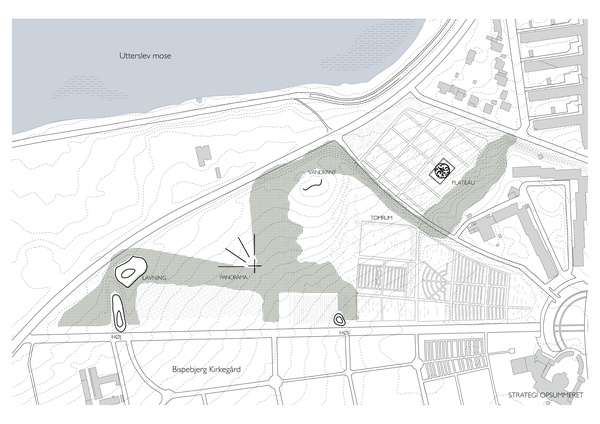

My final project is based on the lack of an alternative to church burial, and converts part of Bispebjerg Cemetery into a secular burial ground. The burial ground is located between the natural area of Utterslev Mose in the north and the traditional cemetery and city to the south. The tension between city and nature plays a key role in the project and was a catalyst for my process and method.

What was your motivation for this project in particular?

For a long time I had been thinking about the lack of obvious rites and ceremonies for when a non-believer dies. How should you actually be buried, if you are not a member of the established church? Not to mention where? What options are there? The cemetery and the chapel form our culture’s current setting for the rituals and ceremonies related to death. For the survivors who are in mourning and under pressure of time, it already takes a huge amount of energy to organise a meaningful farewell ceremony and, given the lack of established options, many non-believers end up using the Church’s spaces anyway. That is why we need new sites for burial outside the established Church, and I wanted to create a meaningful alternative to ecclesiastical burial and the associated memorial rituals. Non-believers also need shared traditions and rituals to commemorate the transition between life and death, and the demand for new funerary forms and rituals is on the rise. In particular, forest burial is gaining ground in several places in the country. If religion cannot offer solace for humans, nature may offer comfort and meaning.

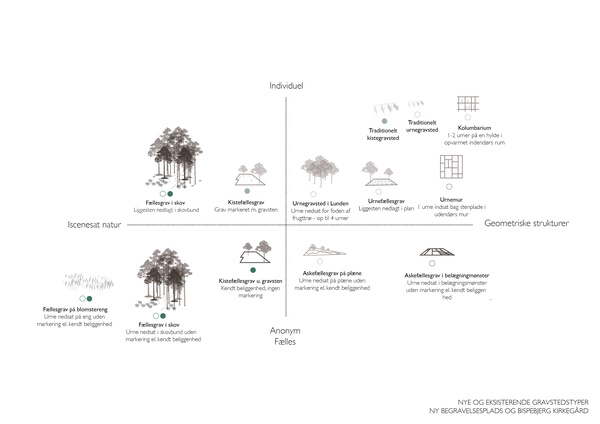

I believe that one of the first steps towards equality in terms of our views on life is to come up with an alternative to ecclesiastical burial. My idea is for a secular burial ground to generate common commemorative rituals and ways of grieving together, outside the context of a church. The fact that most people today choose cremation rather than burial is freeing up a lot of space in cemeteries. This paves the way for forming new burial areas with nature as designer, as opposed to geometric structures that are adapted to the measurements of coffins.

For whom do you imagine your degree project will make a difference?

I think that the need for a place to be buried without attachment to a church will fall into place the moment the alternative can be found. More than 40% of the population of Copenhagen are not members of the established Church, yet the majority of them are buried in a Christian cemetery and with a ceremony in a Christian chapel. Even though cemeteries – particularly the large urban cemeteries – generally speaking are very diverse with a multitude of sections for people with different outlooks and nationalities, the traditional cemetery is still based on the symbolism and idiom of Christianity. By creating a completely different burial place based on nature rather than religion, I believe we could create a sense of security for many people with an outlook other than Christian: a sense of security stemming from certainty that there is also a special place for them to be buried and to hold farewell rites, memorial ceremonies etc.

What methods did you use when working on your project?

My project started with a series of registrations of existing cemeteries and cemetery sections: for example Mariebjerg Cemetery in Gentofte, the West Cemetery in Copenhagen, and Skogskyrkogården south of Stockholm.

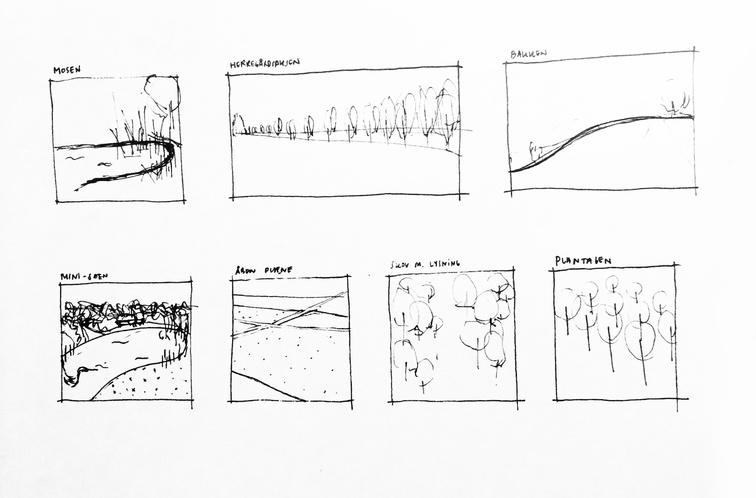

I visited selected sites and registered them on the basis of a phenomenological analysis. I photographed each site in sequences in a continuous movement, and I also drew the spatial progressions in section sketches and wrote about the spatial impact on the site. The purpose was to find out what it was in Christian cemeteries that affected me as a non-believer.

For example, I discovered that the way a visitor moves through a burial place is important in terms of getting into a special, ceremonial mood, and that the spatial shifts and contrasts between light and dark, enclosed and open, up and down, cramped and spacious, place a visitor in a special atmosphere. Something different from everyday life.

It was incredibly rewarding and important to talk with people who work according to the same values and goals of equality and parity, which played a key role in my project. I had inspiring and enlightening meetings with Ole Morten Nygård, a ceremony leader for the Humanist Society and Anna Balk-Møller, a spokesperson for CeremoniRum.

I also needed to get an in-depth knowledge of the history of Bispebjerg Cemetery’s evolution, its connection to Utterslev Mose over the years and the general way the Cemetery is divided up. I received great help from Stine Helweg, the City of Copenhagen’s Cemetery Supervisor. She readily answered my many questions and granted me access to the Cemetery’s archives.

To which UN goals does your project relate, and why?

My project relates particularly to UN global goal No. 10 for less inequality, due to the project’s vision of equality of outlook in society. I believe that there should be equal opportunities and privileges in terms of burial and memorial ceremonies for all, whatever their outlook on life. A secular burial place in Copenhagen would signal inclusiveness and equality and take seriously any individual’s universal right to a dignified burial.

What are the most enjoyable and the most difficult aspects of the way you work on architecture?

The most fun aspect of working with architecture and landscape is discovering the actual needs of a particular site. The societal issue that needs to be tackled? For whom it needs to be tackled and how it can make most sense and be most relevant.

Being a problem solver and coordinator of many different wishes and needs and consolidating them into an integrated solution is the most fun aspect, but also the most difficult. Discussion gives rise to both creativity and innovation, but also doubt. Your own ideas and approaches are challenged. There is no correct answer in architecture. Everything is always up for discussion. It requires both great responsiveness and security to arrive at the best solution.

What sort of development potential do you think your final project has?

I think there are great opportunities for development in the whole debate about burial and ceremonial spaces for non-believers. In the regular discussions I had with people about my project, the question was often whether the project was exclusively for atheists, and that religious people should not be buried there. But I strongly believe in inclusiveness and inclusion, rather than exclusion. A secular burial ceremony does not exclude anyone. You can be buried or have a funeral in this context, if it is meaningful for you. For a big city like Copenhagen, I believe that it is a quite natural step to develop a burial place that includes all citizens and with a strong connection to nature. The city could make an international name for itself and become a landmark for openness, tolerance and coexistence.

What do you think is your greatest strength as a KADK architecture graduate?

My greatest strength as an architect is the clear communication of a special narrative and a strong analytical approach to work on societal issues. I have great empathy and find it exciting and rewarding to collaborate with other professional competencies and users to come up with the best solution.