Master’s Graduation Project 2015: Transforming the Kähler Factory

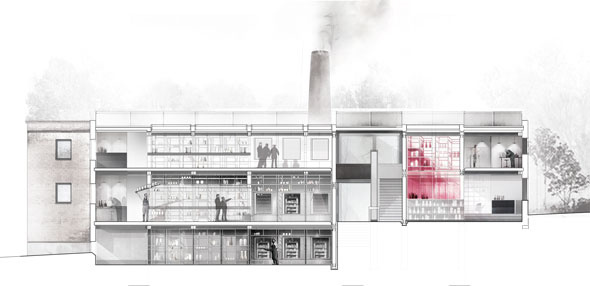

Working with architecture at a professional level means working exhaustively with materials and knowing which materials will suit a building, its lines, its function and its history. Architect Elisabeth Johnson transformed the old Kähler factory in Næstved into a multifunctional ceramics centre. This new centre is state of the art, yet its specially developed ceramic cladding also keeps the Kähler history alive.

What is your Master’s graduation project about?

My Master’s graduation project transforms the old Kähler ceramics factory in Næstved into a ceramics centre housing the headquarters of the Kähler company, a new ceramics studio and accommodation for both upcoming and established artists. By sharing space and facilities, ceramic designers and those who work with the actual production process are able to learn from each other, thereby enhancing and providing inspiration for the design process and the development of new prototypes.

Because neither the factory nor the company are now owned by the Kähler family, the idea behind the ceramics centre is also to inspire the current owners of the company to draw more on the original Kähler heritage and history.

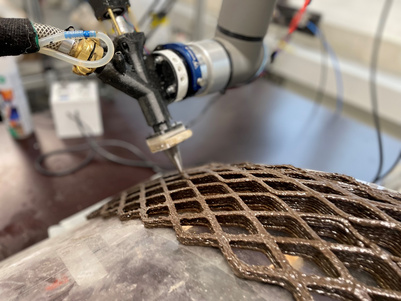

The project stems from my fascination with the relationship between ceramics and architecture, and how materials should be selected and used to complement each other and form a synergy with the architectural design. Part of the project specifically deals with the ceramic material. I experimented with some of the original working methods and techniques used by Kähler in order to develop a ceramic façade element that runs consistently throughout my redesign of the factory.

Why did you choose to collaborate with a partner from a field other than architecture?

During the course of my project, I established an interdisciplinary collaboration with Bente Skjøtgaard, a ceramic artist and teacher at the School of Design. We developed new ceramic glazes that made reference to the original lustre glazes used by Kähler. These glazes will be used in the overall design transformation.

By collaborating with Bente, I learned about the conditions and functionalities required for ceramics production as well as the importance of co-operation in general. This, and the fundamental understanding of materials gained by producing my own ceramic objects in the workshop, ultimately resulted in a coherent project that explored both architecture and ceramics, a project, in which architecture and ceramics constantly challenge each other.

What is most fun and what things are hardest when working on architecture in the way that you do?

The thing that is most fun and the thing that is hardest are the same: my fascination with the interplay between ceramics and architecture. Similarly, the change of pace that comes from alternating between working with ceramics and architecture is both challenging and satisfying.

When you work with ceramics, you need to be patient and take great care throughout the entire process. You literally get the chance to get your hands on the material, something that provides a greater understanding of the material that you have chosen, and which in turn enables material and design to challenge each other. I actually think that a main reason for the success of my project is the fact that I was able to switch between drawing on the computer and making actual models.

Working with ceramics is also characterised by a constant factor of uncertainty. At any time, something can happen to destroy your work, for example during the drying or firing processes, and this can be really exasperating. But when you succeed and you hold the desired result in your hands, it all seems worth it.

Ceramics takes time and you need to think ahead and be efficient and well organised. It took me four weeks to produce the final objects, and this was something that I had to take into consideration during my initial planning.

What do you consider to be your greatest strength as a KADK architecture graduate?

Throughout my Master’s course, I was encouraged to find where my own personal passion lies in architecture and to explore this passion at all levels and scales of architectural design (from 1: 500 to 1:1). This, along with a unique attention to materials and craftsmanship in architecture, has shaped me as an architect and given me my own unique focus.

Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

I would really love to continue researching into the field of ceramics as an architectural material, and also to continue my study of the lustre glaze together with Bente.

I will continue to test the limits of what exactly it is that constitutes architecture today, and see if it is possible to take back some of the design-management control that over the years architects have lost. Maybe we could get more architects to produce their own materials, thereby challenging architecture even more.

Maybe I could also continue my research as a PhD student at the Design School SuperFormLab at the Department of Product Design. That would be really great.